On the day we officially launched Kolar’s Gold I happened to be halfway through my first visit to India, staying in Bangalore. As luck would have it a colleague in the UK had put me in touch with a wonderful couple, Frederick and Reeba, who are relations of his from Bangalore. They generously offered to take me and my wife Jill to KGF, the Kolar Gold Fields.

The morning of the launch saw us hurtling along the highway out of Bangalore in Frederick’s little blue car. Pulling off the motorway we traveled along unmade country roads between boulder-strewn hills, skinny livestock roaming in the fields between and regularly straying into the road. As we neared KGF Frederick told us that a house in this area costs the equivalent of 5-10 pence per month to rent.

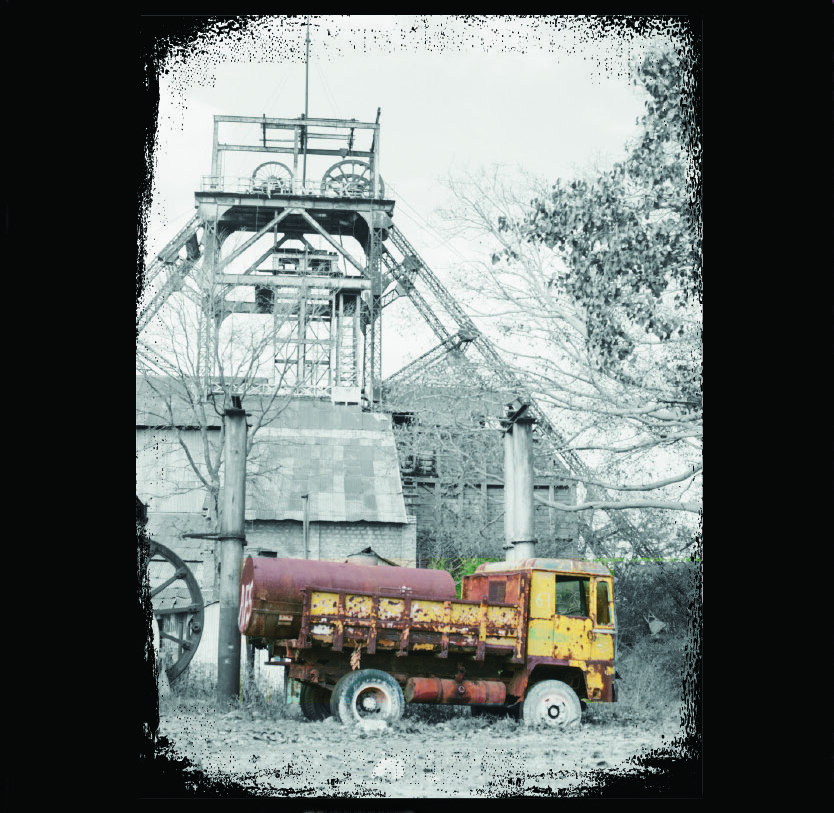

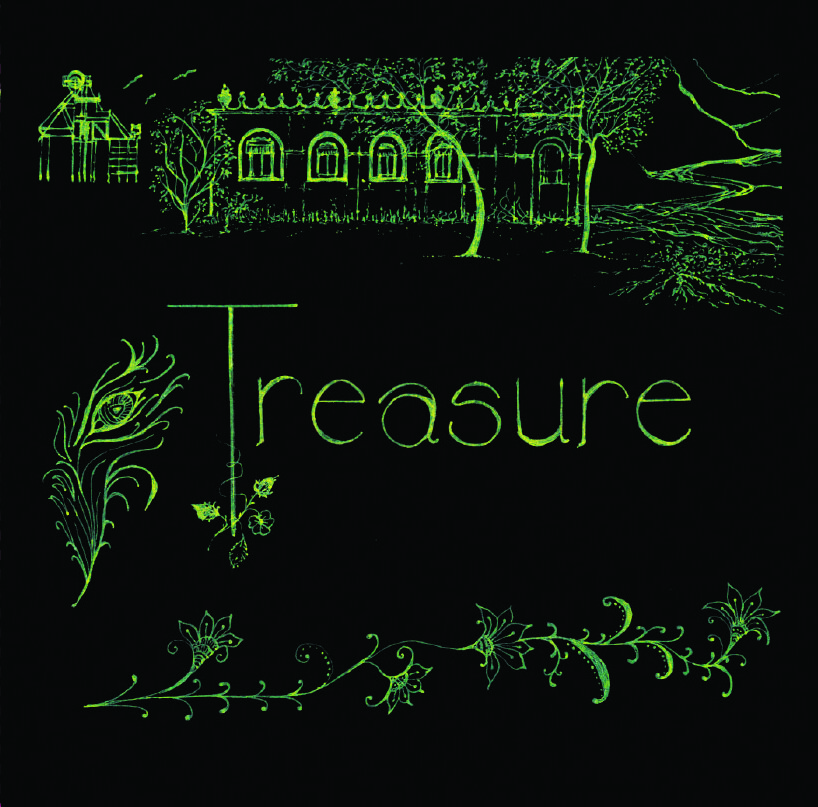

The hills receded and the fields became interspersed with miner’s cottages; small concrete dwellings of one or two rooms. Colourful stalls sprang up along the roadside, announcing our entry into KGF proper. The buildings, still very humble, began to display a markedly European influence as we pulled over to await our rendezvous with Pastor Benny, who Frederick had appointed as our local guide. We followed Benny’s van through KGF, past houses, churches and shops which spread out across the gently rolling countryside. Cresting a hill, we saw the first of many gaunt hoist towers which crown the disused mineshafts, gradually rusting away.

A short way up a dusty track we stopped at Pastor Benny’s church, built by one of his forbears in the colonial era and pastored by subsequent generations of his family ever since. Stepping into the pleasantly cool interior we were greeted by Benny’s father who had been a mining safety inspector in the 60s. Like everyone we were to meet on this visit, Benny’s father spoke wistfully and at length on KGF’s glory days, when it had been at the forefront of technological and social advances. On the relationship between Indian and European residents, he was harder to draw. On the whole he painted a positive picture of a shared culture and pastimes; the ‘Britishers’ did indeed get all the best jobs and authority positions but also often shared in the dangers faced by the Tamil miners. Personally, he greatly appreciated the legacy of the British in terms of the impressive number of well attended churches dotted around KGF.

‘So would you say the two cultures rubbed along well?’ I asked

He nodded, ‘’Yes, of course.’

‘But would you say you were friends?’ Jill prodded, ‘Did you have British friends?’

He gave a small laugh and shook his head.

I’ve heard ‘The British Raj’ variously being feted as a benevolent endeavour, benefiting both parties, and more recently vilified as callous, exploitative oppression. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the truth as expressed by the Indians I spoke to is somewhere in between. Those at KGF were incredibly proud of the advances their mixed community had made during the colonial era. There was much talk of technology, trains, roads and workers’ safety which obviously benefited the local workforce as well as the European former mine owners.

With these thoughts whirring around my head, we set off on Benny’s tour of KGF. We drove down the track past Benny’s house, a gracious stone barn of a building which had been divided into small apartments for European mining families. Before Benny’s family moved in, his apartment had been occupied by an Italian family. On the other side of the road was a straggle of the one or two room concrete shelters which had housed the Tamil workers, unkempt and overgrown.

The track wound down to a shaded valley housing the ‘Crushing House’, where machines used to pound the rock from the mine down into smaller fragments. Behind the massive rusty gates, and the grim security guard, towered an imposing stone building adorned with rusty fittings and a raised conveyer, spanning the valley, to transport the pounded stone to an unseen destination. When Benny was young, he would sit on the high bank listening to the great machines, watching the stream of rock emerge from the conveyer belt opening cut into the building’s gable.

Joined by an inquisitive gaggle of local schoolboys, we wandered out of the valley and up to KGF train station. We stood around chatting to the boys (who spoke amazing English) and watching the goats wander over the tracks. Frederick told us that the train from KGF to Bangalore is one of the longest in the whole of Asia. There is now hardly any work in KGF, and so several thousand people cram onto the morning train to work in Bangalore each day, returning at 9 or 10pm.

We hopped back in the car and went to look at several of the old shaft entrances – decaying iron headgear squatting over impossibly deep shafts guarded by unsmiling security guards. I tried to ignore the baleful gaze of one such custodian as I peered through the gates of ‘Edgar’s Shaft’. In front of the shaft was a small and much decayed lorry with a tank on the back. This, Benny explained, was the truck that brought water to the residents of KGF when he was young. Water is a big problem faced by KGF residents because the mines spread underground for miles and miles across the area, which means it is not possible to use bore holes.

At another of the shafts we could see a collection of rusted vehicles gradually being overcome by vegetation. Benny pointed out two old buses which in their way had both had quite a bearing on his life. One took him to school as a child, and the other was used to transport the gold out of KGF.

I found it really poignant walking around with this man – so many of his memories were given physical form in the buildings and machinery we saw. But they are all gradually decaying, reminders perhaps of happier times which have now past. Nowhere was this more obvious than at the KGF Club.

I was loitering outside trying to get a good photo when the uniformed caretaker approached our little group. To my surprise he offered to show us around and so we walked through the attractive gardens and up to the front door.

Walking round the KGF club was fascinating, emotive and faintly disquieting. From what I could tell it is near enough preserved as it would have been when India became independent, but the custodians now have limited resources to maintain such a grand complex.

As we were shown through the bar to the indoor badminton court, we were confronted with walls and walls of black and white photos of the KGF Club's leading lights.

‘Have a look at the photos.' Said Benny 'You might find a relative!'

He might have been joking, but as I continued perusing the many photos of white men, I was all too aware that Benny's race would have initially prevented him from joining his club.

As our tour drew to a close I sat quietly in Frederick's car and tried to process all I'd seen. I don't really know what I'd expected, but it was certainly nothing like the potent mix of nostalgia, pride, poverty, beauty and ruin that I had found. In the midst of so many conflicting emotions there were some things I was completely clear on; in many ways KGF was one of the saddest places I have been to, but also it was one of the most beautiful and welcoming, with immeasurable pride in it's past and so much goodwill from all those who are connected with it. In short, I had well and truly fallen in love with this place.